The war between sunshine and authentic investigative journalism

Also broadly in this grouping is the new owner of Independent Newspapers, Iqbal Survé of Sekunjalo, who is saying he wants a more positive and patriotic narrative in his papers.

It is a view one hears frequently from government communicators, who bemoan their difficulty in getting their stories into media they see as quick to criticise and slow to praise. They want to counter the Afro-pessimism that runs through a good deal of media coverage, as well as the tendency to favour "sensationalised" bad news. Critics of this approach say it continues the tradition of the apartheid SABC (when it was a state rather than a public broadcaster) and much of the Afrikaans media, which played down news that was embarrassing for the government of the day. It is no coincidence that Chinese investment is pouring into this kind of journalism, coming from a country that keeps its media within tight parameters, promoting what it sees as its national interest, or that our government threatens to use its advertising to encourage this approach.

As a result, we are seeing more and more of this kind of reporting.

On the other side, there is an adversarial style of journalism, which sees its primary role as a watchdog over those who wield power. This view is based on the media as a "fourth estate", there to counter the power of the state. This is a more aggressive style of journalism, found in those media that run investigative teams, such as the Mail & Guardian and the Sunday Times. In South Africa, there is a rich history of this kind of journalism, starting with Thomas Pringle and John Fairbairn in the 19th century, through to the great writers of Drum magazine in the 1950s, such as Henry Nxumalo and Nat Nakasa. There was Ruth First and other left-wing writers in the same period, and the alternative anti-apartheid media of the 1980s (such as the Weekly Mail and New Nation), and the liberal Rand Daily Mail of the 1960s and 1970s.

Critics of this view say it encourages cynicism by harping on problems and seldom offering solutions. They say journalists pretend to be objective watchdogs, ignoring the fact that they usually take sides and — because media are businesses — often the side of business. Because this kind of journalism can be harshly critical, there are those who are quick to label it "anti-transformation".

Journalists often like to say they just follow and reflect the news, telling people what is going on and what they need to know. But this is a faux naivete, pretending they are not making choices about news values all along the way.

There are those who seek a middle path. What is often called civic journalism tries to encourage citizen engagement by pointing to solutions, or giving people ways to respond to problems. A good example of this is the Lead SA campaign.

I think journalism is at its most useful when it is challenging, probing and disruptive and the main problem with the kind of reporting we are seeing on the SABC is that it is terminally boring. I want to revel in the noisy, disorderly contestation of a vuvuzela democracy. Interestingly, this is what the SABC’s code of conduct allows for, encouraging a contestation of different views. And it is the approach favoured by Nelson Mandela, who spoke in favour of investigative reporting. "Critical, independent and investigative media (are) the lifeblood of any democracy," he said in 1992. Mandela remembered that postcolonial Africa suffered from obedient media, which tolerated bad governance, and the lack of an outspoken watchdog press.

In South Africa, these two traditions are fighting it out, which means that you, the audience, can choose.

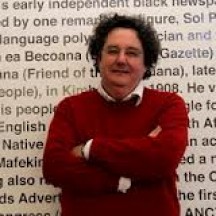

• Harber is Caxton professor of journalism at the University of the Witwatersrand.