Shuttleworth's exchange control case headed for Concourt this week

It is an apartheid-era document with rules for everything from donations to missionaries to the amount of jewellery it is appropriate to wear when leaving the country.

The manual, and exchange control in general, continues to be attacked by IT billionaire Mark Shuttleworth who has been fighting it in the courts.

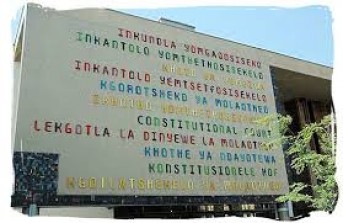

This week it ends up in the Constitutional Court where I hope some finality will be found. There is no doubt some parts of the exchange control manual are unconstitutional. That ruling was made by the High Court, though the Supreme Court of Appeal overruled it on the grounds that the general constitutionality of exchange control was not relevant to Mr Shuttleworth’s case.

It found only the R250m levy the South African Reserve Bank charged him was unconstitutional and ruled it should be paid back with interest (which he promised to put into a fund to support others’ court actions against the government).

The Bank is appealing against that decision while Mr Shuttleworth is appealing against the general constitutionality of exchange control. Whatever the outcome, it is clear that government has woken up to the need to do something about the archaic rules, which are based on an act written in the 1930s. "Simplified" apparently means making the manual easier to use, but also making it constitutional.

Apart from reviewing the manual, the budget also announced increases in the foreign exchange allowances for individuals and businesses wanting to invest overseas. Firms can now invest R1bn a year, twice the previous amount. Emigrating South Africans can now take R10m a year, up from R4m.

Individuals can still only send R1m a year offshore, the same as previously despite the weaker rand, but complex subcategories within this amount have been scrapped. While details are still to be published, that appears to mean that individuals will be able to send R1m offshore without the headache of having to show travel documents.

These are all good steps in the right direction by government. But the banking industry, which enjoys a cosy oligopoly on exchange control services thanks to the exchange control regime, has been pretty slow in filling the space that relaxed regulations have opened.

I once again experienced the complete lack of interest of my bank (which I won’t name) in helping customers with foreign exchange when I asked it to transfer money overseas in advance of a trip. The very helpful lady at the counter advised me to rather go and use American Express. She was right. American Express gave me a better rate at lower fees and got the money there quicker than my bank could have.

Whenever I point out how bad the banks are at exchange control services for their customers, I get an e-mail from someone at First National Bank (FNB) telling me they are the exception — their clients can apparently send money overseas through online banking. So to avoid that e-mail, I acknowledge here that FNB is ahead of the game. But the rest of the banking market should, frankly, catch a wake up. The exchange control regime has changed, but the banks behave as if it hasn’t.

• Talking of catching a wake up, on Sunday the tax-free savings account regime became a reality. The smart money will want to use the R30,000 allowance as soon as possible to open a tax-free savings account. The returns earned on that money will be tax free, so the sooner you get it into an account the better. But the only two institutions that had publicised accounts before the deadline were Investec and Old Mutual subsidiary 22seven. Investec is offering a fixed deposit and 22seven two Old Mutual unit trusts.

The rest of the market has so far been remarkably reticent. In part this is because Treasury held out until a week ago before publishing final regulations, but I suspect it is also because those regulations tightly constrain the fees that can be charged on such accounts. Even though the accounts are a great product, they are not as lucrative as the complex policies and other products our savings industry pushes onto their clients.