Land reform fears are overblown

Parliamentary discussions on land reform have prompted much breathless commentary. But, while the proposed changes remain unclear, a mushy compromise is more likely than a Zimbabwe-style land grab, says London-based economist John Ashbourne of Capital Economics.

Parliamentary discussions on land reform have prompted much breathless commentary. But, while the proposed changes remain unclear, a mushy compromise is more likely than a Zimbabwe-style land grab, says London-based economist John Ashbourne of Capital Economics.Last week, South Africa’s parliament established a committee to examine constitutional changes allowing for the expropriation of land “without compensation”. The committee will report back by 31st August.

The move has sparked fears that the ruling African National Congress (ANC) is moving left, with some making comparisons with Robert Mugabe. This is a rapid turnaround given that the election of President Cyril Ramaphosa was widely seen as a sign that the party was adopting more investor-friendly policies.

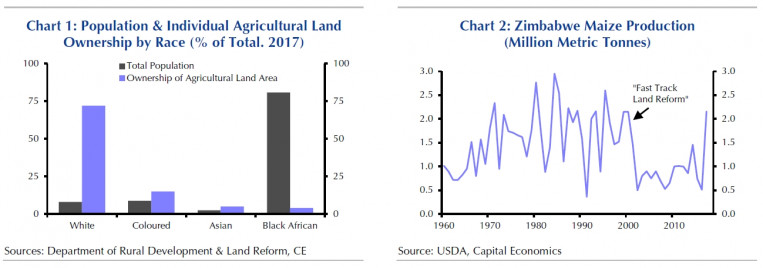

The political salience of land far exceeds the economic heft of the agricultural sector (just 2% of GDP). Apartheid-era laws disenfranchised Black farmers, consolidating the ownership of agricultural land in the hands of the White minority. Ongoing programmes to transfer 30% of agricultural land to Black owners using a “willing seller, willing buyer” model have stalled. Of the 40% owned by individuals, almost three quarters is still controlled by White South Africans, who make up just 8% of the population. (See Chart 1.) (The majority of privately-held land is owned by firms or trusts, making a full accounting difficult.)

The current proposal may – like many before it – peter out due to political divisions. After all, last week’s vote only established a committee to investigate possible solutions. A previous expropriation act (albeit one that included compensation) was actually passed in 2016, but became bogged down in consultations and was never enacted. Just this week, the ANC postponed plans to nationalise the Reserve Bank.

Indeed, a failure to agree is particularly likely in this case. Many within the divided ANC oppose this move – particularly traditional leaders who fear that reforms might weaken their hold over communally-held land. And constitutional amendments require a supermajority in parliament, forcing the ANC to work with opposition parties. Most will refuse any change, while the leftist Economic Freedom Fighters party wants to go farther and transfer all land ownership to the state, a ‘great leap’ which the ANC opposes.

If the constitution is changed, it will probably be via a mushy compromise allowing for expropriation in very limited circumstances. Last week’s parliamentary motion echoed President Ramaphosa’s line that expropriation should only be used when it “increases agricultural production [and] improves food security”, a standard that would preclude rapid, wholesale transfers. ANC officials have suggested that expropriations might target unused land, or grant individual title to community-held trusts.

Indeed, any law that results from the current process should be seen as an incremental expansion of the state’s existing land reform powers. Land reform is, after all, an ongoing process in South Africa.

Zimbabwe’s sudden and chaotic land grab did, admittedly, result in an economic crisis. (See Chart 2.) But this is the exception rather than the rule; emerging markets from India to Korea embarked on more orderly processes in the 1950s and 1960s. And any reforms in South Africa would occur gradually and in the context of open parliamentary debate and a robust legal system. Nor, given the particular political salience of land rights, should land reform be seen as the beginning of an inevitable shift towards nationalisation in other areas of the economy.